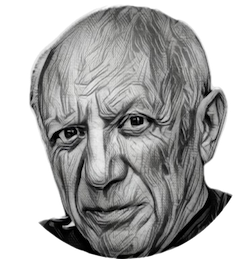

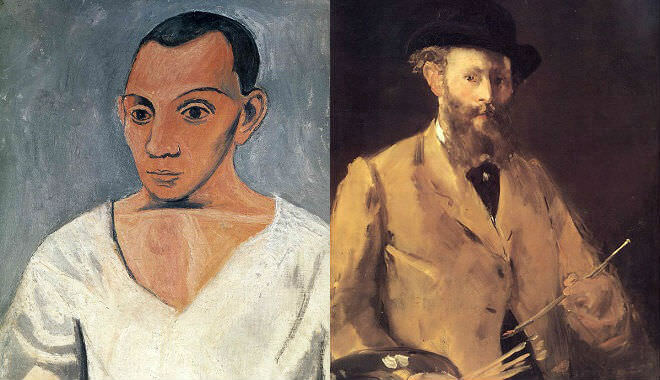

Picasso and Edouard Manet

On the back of an envelope from the Simon Gallery, probably in 1932, Picasso wrote: "When I see Manet's Lunch on the Grass I tell myself there is pain ahead". Written comments by Picasso on painters and their works are

extremely rare, and this one even more unusual in that it mentions one painting in particular. It projects the artist into an unknown future, but a future nevertheless outlined by this looming encounter.

Throughout his career, Picasso went back to El Greco, Caravaggio, Diego Velazquez,

Rembrandt, David, Eugene Delacroix and Gustave Courbet. But his experiment with

Manet's paintings was, without doubt, the most profound and the most complex he ever undertook.

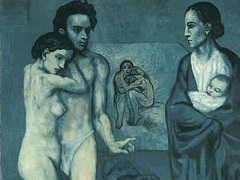

1863 : Lunch on the Grass

Of all the works Picasso selected for his "variations", The Lunch on the Grass was the nearest to him chronologically. This painting had still not shaken off the scandalous reputation it had attracted at the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Manet is a modern "old master". According to Georges Bataille, the modernity of Manet and his "subversion" were what mattered most to Picasso, who, since he presented the Demoiselles d'Avignon in 1907, now bore the full force of the slings and arrows of artistic fortune.

The Lunch on the Grass is a painting with several overlaid themes:

- The reference to the old masters, Manet having taken his inspiration from Titian's Concert champêtre in the Musée du Louvre, and from The Judgement of Paris, an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, after Raphael.

- The issue of the nude, "It seems I'll have to paint a nude. Very well then, I'll paint a nude for them", Manet had declared to Antonin Proust.

- The question of the subject, the reason for all the uproar surrounding it. "We cannot regard as chaste a work in which a woman, seated in the woods, surrounded by students in berets and coats, is clothed only in the shadows

of the leaves" (Ernest Chesneau, quoted by Françoise Cachin in Manet, RMN, 1983).

- Finally, the issue of the outdoor setting: the real open air, according to Emile Zola, "In this painting, what one must see [...] is the entire landscape, full of atmosphere, this corner of nature rendered with a simplicity so

accurate...".

Picasso tackles each of these problems in four stages.

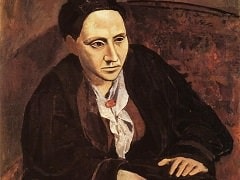

1954 : copy/interpretation/variation

First announced in 1932, it would be twenty-four years before the confrontation began. In 1954, Picasso opened a sketchbook and wrote on the cover: "FIRST drawings/of the Déjeuner sur l'Herbe/1954". The artist completed four

drawings in it, based on the Lunch on the Grass, three of which are dated 26th June 1954. The fourth is dated the 29th.

The first drawing captures the whole composition of the Lunch on the Grass. Everything is there: the landscape, the still life and of course, the four characters: the swimmer, the man on the left holding out his arm (Manet's

brother in law, Ferdinand Leenhoff), the naked woman (Victorine Meurent, the painter's favourite model), and the second man seated behind her (one of Manet's brothers, Eugène or Gustave). In the second study, dated 26th June,

Picasso concentrated on the positioning of the four characters. In the third, he framed the faces of Victorine and Ferdinand. Finally, in the study of 29th June, there is a faithful, naturalistic and even affectionate return

to the four protagonists.

Picasso took over Manet's work, its layout, its protagonists, and their relationship which he had already developed. He copied and interpreted at the same time, immediately moving away from the method he had used to work on

Delacroix's Algerian Women in 1954, or on Velasquez's Las Meninas in 1957. After this taster, he modified the composition and took command, a little like Manet himself had done with the two works that inspired him. The question

of copying and borrowing was just as topical for Picasso as for Manet. Picasso continued to explore Manet's painting, in several episodes, right up until August 1959. There was no pain involved with these many compositions:

joy, amusement, irony and sometimes showmanship. The painter still needed some time to overcome his Manet "anguish".

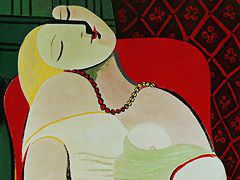

1960: subject

During August 1959, Picasso picked up Lunch on the Grass, again, and based six drawings on it. On 27th February 1960, he produced his first painted version of the Lunch on the Grass. The landscape is lighter,

the swimmer at the back insinuates herself between the two men. Victorine Meurent is blown up like a balloon. Her neighbour is slimmer. Two days and two paintings later, the landscape is reduced to the top of a distant hill

with two trees. Ferdinand, the "Conversationalist", as Douglas Cooper baptised him (Picasso. Les Déjeuners, 1962), is still holding forth before a Victorine who has lost her roundness. His neighbour now smokes a pipe.

At the beginning of March, Picasso started work on two radically different compositions. The first introduced colour, whereas the second went back to the cloisonné style he had developed at the end of the war. It is a severe

painting, in green and black. The characters are isolated, and Picasso closed this first salvo with a completely restructured composition, as if, after having taken the work apart for several weeks, he then gave it back a new

and more solid arrangement.

Picasso changed the position of each of the protagonists. Victorine and the "Conversationalist" provide the main structure of the work. The two other, more incidental characters change roles. They recede or come forward,

according to the version. Picasso's Victorine is no longer Manet's indecent swimmer. She no longer looks at the viewer, but is in silent conversation with the character opposite her. A new scene is set out, similar to the main

theme of Picasso's work in the later years: the dialogue between painter and model, between painter and painting.

Picasso returned to Manet in 1961. Unlike in the last painting of the first series, he seemed to have great fun with the two versions dated 19th April. Victorine is once more a balloon, whereas the swimmer in the background

seems to be paddling around in an inflatable pool, and the "Conversationalist", dressed all in red, resembles a Father Christmas or garden gnome.

In June, Picasso took a serious approach once more. Each takes up his role again in the variation dated the 17th. At the beginning of July, he engraved several plates with the "Conversationalist" duly clothed. But then, Picasso

revolutionised this little world by undressing everyone. In this way, Picasso offers a response to the strangeness of Manet's painting, to the confrontation of a naked woman and clothed men. He seems also to have looked at

Paul Cézanne's view of Manet. Having interpreted Manet's painting, Cézanne undertook many experiments where naked men and women bathed together.

The second man, whom Picasso paints, stretched out on the grass with a book in his hand, is truly Cézannian. The naturist and Cézannian interlude ended on 16th July 1961, with a painting in which Victorine, immoderately

stretched out, huge in size, is leaning towards the big "Conversationalist" like a praying mantis. On 27 July, Picasso again transformed Lunch on the Grass. This time he removed the character next to Victorine, and all

the accessories. The "Conversationalist" has lost his hair, has clearly aged, and without a doubt resembles the painter himself. Picasso enters the painting to talk directly with a Victorine who could be said to resemble his

wife, Jacqueline.

Picasso had never pushed Manet so far as to take his place. He reproduced this new layout five times. Sometimes Victorine-Jacqueline is quite small, submissive before the learned gesture of the "Conversationalist". Sometimes

she is his equal. In a later composition, painted 19 August 1961, Victorine-Jacqueline crushes the "Conversationalist", now a puppet, with her enormous size, whilst the swimmer in the background paddles about in a bath. Irony

is back.

1962: the plein air issue

Several works, engravings, drawings and even a ceramic plate are evidence of Picasso's persistence with the theme of Lunch on the Grass in 1962. However, one aspect of the work remained

to be dealt with; that of the outdoor setting.

Although he took little interest in the landscape, it had not escaped Picasso's notice that, when it came to the great natural setting that Zola had seen in Manet's paintings,

Manet had in fact painted only a theatre set. And, as if wanting to take Manet's aborted intentions to their conclusion, Picasso takes the characters back into the true nature. Between 26th and 31st August 1962, Picasso

produced a series of models of the characters in Lunch on the Grass.

The cardboard figures were designed and folded, and Picasso could place and move each one of them Lunch on the Grass is a game for swingers, it is a relaxed, happy "foursome". The models were photographed in the order that

Manet had chosen. Picasso placed a postcard of Manet's painting alongside them as a reminder of the origin of his composition. To emphasise the natural setting, he made pencil drawings of the trees which would surround the

concrete swimmers. It was Carl Nesjar who produced these models, which in 1966 were placed in the grounds of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

1970: the epilogue

The end of the Picasso-Manet tête-à-tête probably comes with an engraving dated 5 April 1970, entitled Legless Painter in his Studio, painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. Picasso was 89

years old. His painter had not aged, but had become smaller. He still resembled the Conversationalist of the 1961 paintings, but he has taken himself out of the painting. On his left, a woman (Jacqueline) takes up the whole

height of the painting. Both are looking at the composition. Victorine Meurent lets herself go in the arms of her neighbour (clothed). The "Conversationalist" (clothed), disillusioned, is watching a naked woman who was not in

Manet's picture. The swimmer in the background has moved further away. The "Conversationalist" no longer dominates the situation, nor does the painter. The characters and the painting have taken over. This is the final

disruptive twist that Picasso imposes on Manet. And also, on Manet, Giorgione, Raphael, Marcantonio Raimondi and Cézanne - on all painting, in fact.

Manet was the first to break with tradition at the same time as he moved back towards the museums and his masters. Picasso knew that it was precisely between this naked woman, embodying tradition, and the man in modern dress

embodying the painter, even all painters, that the dialogue with the painting began. It is here, perhaps, where the source of the "pain" that Picasso had glimpsed in 1932 resides.