Pablo Later Works - After 1945

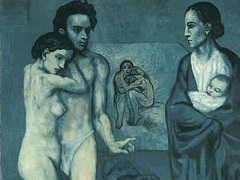

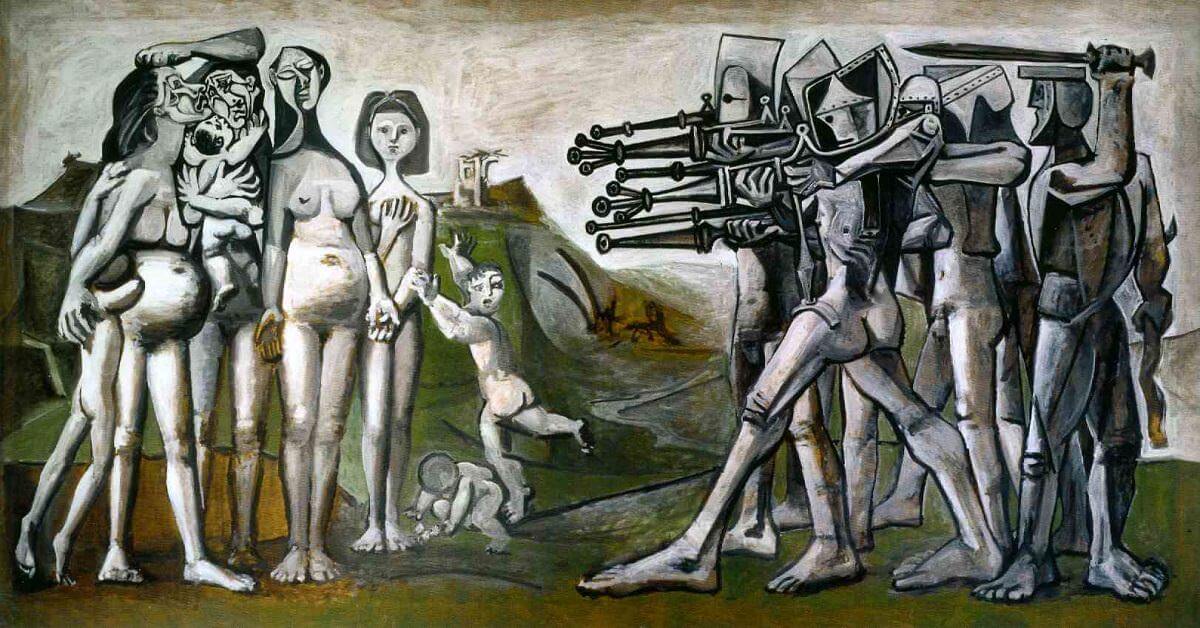

In 1944, after the liberation of Paris, Picasso joined the Communist Party and became an active participant of the Peace Movement. In 1949, the Paris World Peace Conference adopted a dove created by Picasso as the official symbol of the various peace movements. The USSR awarded Picasso the International Stalin Peace Prize twice, once in 1950 and for the second time in 1961 (by this time, the award had been renamed the International Lenin Peace Prize, as a result of De-Stalinization) . He protested against the American intervention in Korea and against the Soviet occupation of Hungary. In his public life, he always expressed humanitarian views.

After WWII, Francoise gave birth to two children: Claude (1947) and Paloma (1949). Paloma is the Spanish word for dove - the girl was named after the peace symbol.

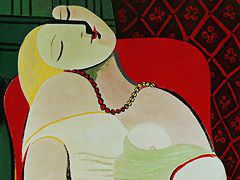

Picasso would not settle down, and more women would come into his life, some coming and going, like Sylvette David; and some staying longer, like Jacqueline Rogue. Picasso would remain sexually active and seeking throughout most of his life; it wasn't that he was looking for something better than what he had had previously; the artist had a passion for the new and untried, evident in his travels, his art and, of course, his women. For him, it was a way of staying young.

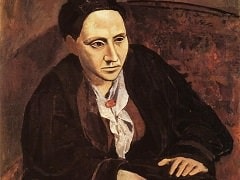

Picasso had a public face, marked by political allegiance, but he was also, in much of his artistic production, pursuing an intensely private path. In winter of 1953, he created an extensive series of 180 drawings know as the Verve suite, depicting circus performers, clowns, Cupid figures and elderly painters studying young female models, suggesting a period of soul-searching. The painter and model motif in particular in this series, as a way of exploring the artist's own person and function, would become a dominant theme in what we now see as "late" work.

By 1955, Picasso had settled in the south of France, and would return to Paris only once more before his death. Living and working in a series of villas and chateaus, he was producing as diverse a range of work as ever, including wooden sculptures and a mural for the UNESCO building in Paris, but a sense of his own artistic identity was paramount.

Picasso's final works were a mixture of styles, his means of expression in constant flux until the end of his life. Devoting his full energies to his work, Picasso became more daring, his works more colorful and expressive, and from 1968 through 1971 he produced a torrent of paintings and hundreds of copperplate etchings. At the time these works were dismissed by most as pornographic fantasies of an impotent old man or the slapdash works of an artist who was past his prime. Only later, after Picasso's death, when the rest of the art world had moved on from abstract expressionism, did the critical community come to see that Picasso had already discovered neo-expressionism and was, as so often before, ahead of his time.